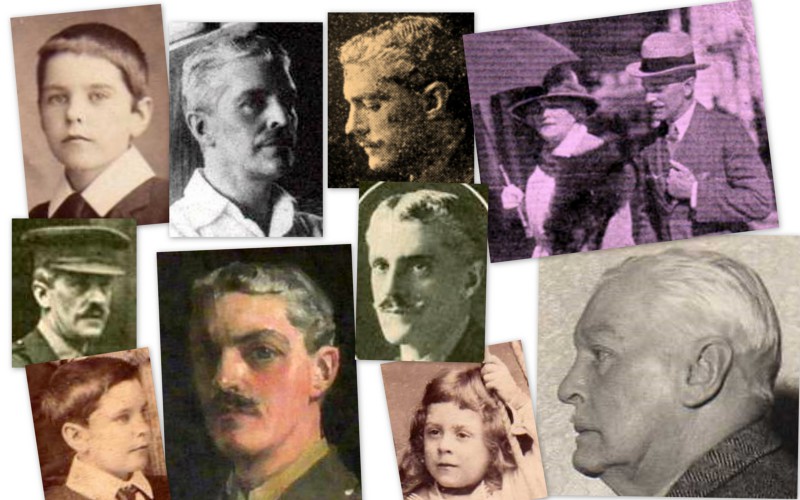

Montie Porch:

a charmed life

The Glastonbury man who married Winston Churchill’s mother

by Roger Parsons

Copyright ©2012, 2019 by Roger Parsons. Published in print and web form by Abbey Press Glastonbury.Engagement and wedding

1917 was another year of service in Africa for Montie. Then early in April 1918, on leave again, he and Jennie were invited to the beautiful estate of Jennie’s brother-in-law, Sir John Leslie, at Castle Leslie in County Monaghan, Ireland. They stayed for two weeks, a happy, comfortable couple who had seemingly come to an unspoken understanding about their future together: many years later, Montie admitted that he couldn’t remember proposing!

As if to seal his life with hers, Montie planted a Glastonbury Thorn in the grounds of Castle Leslie, a thorn that the present Sir John Leslie has recently confirmed still flourishes near the boat house.

Winston, then 44, according to Montie, 41, was “very surprised” by the news of the engagement — without doubt something of an understatement, since it might well be politically embarrassing for him. He was also reported as saying that he hoped marriage wouldn’t become the vogue among ladies of his mother’s age.

For his part, Montie writes to Winston the morning of the wedding on 1 June 1918, reassuring his future son-in-law of his commitment to his mother, and his willingness to share all her difficulties and obligations.

He adds rather poignantly: “It seems almost incredible that today, when our world is in anguish, I should be allowed so much happiness”, and he ends with the promise that he and Winston would be “good friends”.

The wedding was unheralded and simple. The couple arrived at the Register Office in Harrow Road quite unnoticed. Jennie wore a grey coat and skirt and a light-green toque, Montie an officer’s uniform — which may not have been a good move, as we shall see.

The New York Times had announced the engagement on 31 May — as had the London Times — and followed it up with a report on the marriage itself two days later, one day earlier than the London Times:

LADY CHURCHILL WED TO MONTAGU PORCH

DIPLOMAT TO LEAVE FOR NIGERIA, WHERE BRIDE,

FORMER JENNIE JEROME OF NEW YORK, IS TO JOIN HIMSpecial Cable to the New York Times

LONDON, 1st June — Lady Randolph Churchill was married to Montagu Porch at Paddington Registry today. The bridegroom leaves Monday for Nigeria, where he is in civil service. His bride expects to rejoin him in the autumn. It is stated that a wife can obtain a passport to join her husband, when a fiancée in these days is often refused a passport to go out and get married abroad. This is understood to be one reason for Lady Randolph Churchill’s hurried marriage.

Lady Randolph Churchill was formerly Miss Jennie Jerome, daughter of the late Leonard Jerome of this city. She married Lord Randolph Churchill in 1874, the second son of the seventh Duke of Marlborough. He died in 1895 after a brilliant political career, in which his American wife had a great share. Five years after the death of Lord Churchill, she announced her engagement to Lieutenant George Cornwallis-West, a close friend of her son, Winston Churchill. But she was divorced from him in 1914 and the courts allowed her to use her more famous name.

Lady Churchill was one of the first women of the English aristocracy to take up war nursing and has been very active in this work during the present war.

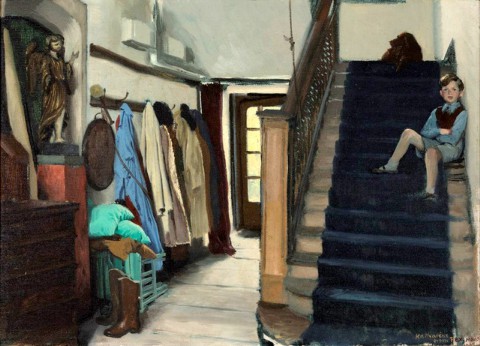

THE WEDDING OF LADY RANDOLPH CHURCHILL : THE BRIDE AND BRIDEGROOM LEAVING AFTER THE CEREMONY.

The wedding of Lady Randolph Churchill and Mr. Montagu Porch took place on Saturday last. Mr. Porch, who is forty-one, belongs to an old English family. He served with the Yeomanry in South Africa, and has since been attached to the Political Department of the Nigerian Government.

He and Lady Randolph are shortly leaving for Nigeria. Originally Miss Jennie Jerome, of New York, she married Lord Randolph Churchill in 1874. He died in 1895, and in 1900 she married Mr. George Cornwallis-West, whom she divorced in 1913. [Photograph by Farringdon Photo. Co.]

LADY RANDOLPH CHURCHILL MARRIES AGAIN

(INSET, MR. MONTAGU PHIPPEN PORCH, THE BRIDEGROOM)

Lady Randolph Churchill’s engagement to Mr. Montagu Phippen Porch was announced at the end of last week, and it is understood that the marriage will take place very shortly. [In fact it had happened on 1 June.]

Before she married the late Lord Randolph Churchill in 1874 Lady Randolph was Miss Jennie Jerome of New York. She subsequently married Mr. George Cornwallis-West, whom she divorced. Mr. Montagu Porch is the son of a Bengal civil servant. He served in the Imperial Yeomanry in the South African War and has been British Resident in Northern Nigeria.

The Times reported the marriage on Monday 3 June, in a little more detail but with no mention of Jennie’s American background.

The Tatler printed their photo on its front page two days later.

It was reported that the witnesses signed the register in the following order: Winston, Sir John Leslie, Mrs Clara Moreton Frewen, Mrs Winston Churchill, Lady Islington, Miss Winifred Maud Porch, Lady Gwendoline Churchill (wife of Winston’s brother, Jack) and Lady Sarah Wilson.

The story goes that, having signed the register, Winston said to Montie, “I know you’ll never regret you married her”, which, Montie said many years later, he never did.

Afterwards, the bride and the bridegroom left for a destination which was not disclosed — one report says this was Windsor, but there is a strong suggestion that the newlyweds went on to Weston-super-Mare to stay in Montie’s house at St George’s, one of several properties he had there, which enabled him to introduce his new bride to his mother.

Trouble on all fronts

However, Montie got into hot water with the authorities over his absence, since he did not report to Crown Agents on arriving back in England, as officers were requested to do. He was without doubt totally absorbed by his love for Jennie and was quite prepared to bend the rules to please her.

To complicate matters further, he had applied in March that year for permission to accept an appointment to the Hedjaz Mission, which was organizing the Arab revolt against the Turks. However, he failed to mention that his leave had expired, and in any event the Governor-General of Nigeria refused to release Montie because of a shortage of staff.

That wasn’t the only problem. Jennie was determined to marry a soldier in uniform as she had with George Cornwallis-West. Montie obliged by obtaining an officer’s uniform and added in the marriage register after his name “Lieutenant, West African Frontier Force”, which was stretching a point somewhat by claiming a title he had not used since at least 1916!

Eventually, newspapers and magazines with photographs of the happy pair reached Zaria, to the obvious displeasure of the Commandant of the depot of the Nigeria Regiment, who threatened to prosecute Montie for wearing a uniform to which he was not entitled. Montie responded that he had been in effect an officer with the Cameroons column, and would have been an officer with the Hedjaz Mission had he been allowed to join it. He also explained his own excitement at his wedding, and Jennie’s insistence!

While these matters were being considered, Montie did return to Nigeria, although without Jennie, who was not allowed to accompany him, civilian travel being restricted for the duration of the war. Jennie is said to have tried repeatedly to get permission to go but was refused because of submarine peril. This was certainly the line that Montie took later in life but there were those who felt that, if it had been her former lover Count Kinsky or ex-husband George Cornwallis-West, Jennie would have found a way to get there. However, had she done so, there is little doubt that she would have not enjoyed the heat!

Indeed, it was fortunate that Jennie had to stay in England, since immediately on his arrival in Nigeria Montie had to face a further legal imbroglio to do with an embittered cook he had dismissed. The serious allegations levelled against Montie were dismissed but not long afterwards he was charged with assault for getting his servants to exact physical revenge on the man. Montie pleaded guilty, was severely censured by the Colonial Civil Service and, his reputation tarnished, was ordered by the Governor of Nigeria to leave the country forthwith.

This Montie eventually did, sailing from Lagos late in July, with the Governor’s secretary almost waving him off from the quayside! This was the end of Montie’s career in the Colonial Service although it is not clear whether he resigned or was compulsorily retired.

Public glare in London

Back in London and doubtless happy to be rid of all the unpleasant business abroad, a world away in more than one sense from his new life with her, Montie set up home with Jennie at 8 Westbourne Street, near Kensington Gardens, a prestigious house on which he had bought the lease — Jennie could put all her energies into redecorating and refurbishing it.

But life in the limelight with Jennie was not a comfortable one for Montie: a whole host of anecdotes and smart comments about them began doing the rounds in all the fashionable circles. One cruel but witty observer had already announced around the time of the wedding that the only way he could imagine the newlyweds spending their evenings would be a variant on the Arabian Nights, she regaling him nightly with the account of her amours, in a collection known as the Nigerian Nights!

Such remarks as these soon spread all over the London dinner-party circuit, and even Jennie joked to Montie about it, repeating the famous series of puns: “Miss Jerome went up the Church Hill, to the West, into the Porch.” Jennie herself produced some memorable aphorisms, including the much quoted “He has a future and I have a past, so we should be all right.”

As to all the unpleasant talk, she would counter them with ripostes such as “They say. What do they say? Let them say!”, confident in the belief that she was the envy of all the girls for marrying the “handsomest man in London”. In fact many of her friends remarked upon how contented Jennie was with her third marriage and how much younger she was looking.

Indeed, although most of her contemporaries had slipped into social retirement by the end of the Great War, Jennie was, at 64, as young in spirit as her rather conservative husband and certainly not for changing her busy, exciting lifestyle.

So 1919 and 1920 were filled with places (such as Ireland, including a return to Castle Leslie, and France) and people — famous, exciting people such as Stravinsky, Picasso, Ravel, Proust, James Joyce, some of whom later visited Jennie and Montie in London.

Old friends, too, such as Queen Alexandra, came to visit — when Montie had to telephone for a constable to be outside — and the younger set, like newlyweds Zelda and F. Scott Fitzgerald. (Fitzgerald dedicated his second novel The Beautiful and the Damned to Jennie’s nephew, Shane Leslie.)

On 18 June 1920 Jennie and Montie are reported by the Times as being in the Royal Enclosure at the Ascot Gold Cup, Jennie in a gown of white lace over black, with hanging sleeves of black net.

It was clear to everyone how exhilarated Montie was by his exciting new life, as if he had come out of a cocoon into a different world. However, after more than a year of fun and fascinating people, Montie now wanted to take on some work of his own. Moreover, he and Jennie needed money.

The Gold Coast and tragedy

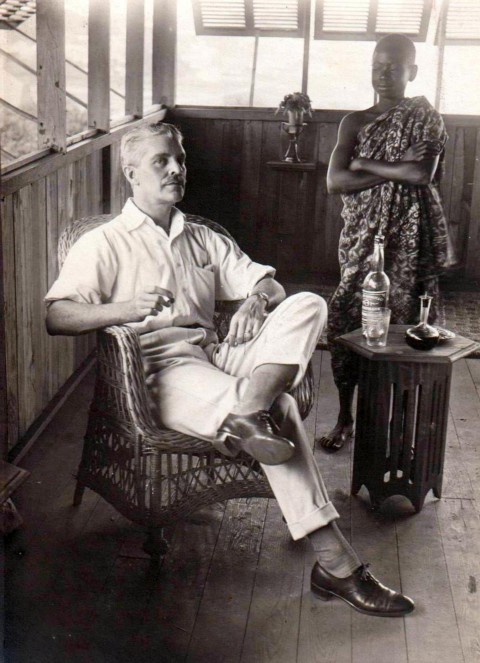

Montie’s qualifications for a career were few, but for a man who knew the continent, Africa was full of opportunities, particularly in the Gold Coast (now Ghana), where trade in gold, palm products, rubber and cocoa, for the burgeoning confectionery industry in Europe, made it an exciting and potentially profitable country to invest in — so much so that Jennie’s sons, Winston and Jack, decided to finance Montie’s exploratory trip there.

Loath as he was to leave Jennie, Montie was glad not only to make some money to support his wife’s extravagant lifestyle but also to get away from the continuing snubs and sneers he had to endure at Jennie’s side. He is recorded as saying that he preferred the bullets of the Boer War or the flies of the Gold Coast to the stings of the snobs in a London drawing room, although the quote also emerged as “Better the mosquitoes of Africa than the pricks of London drawing rooms.”

He left England in the spring of 1921, and as he went on board ship, Montie found in his coat pocket a letter from Jennie that he always treasured:

My darling,

Bless you and au revoir and I love you better than anything in the world and shall try to do all those things you want me to do in your absence.

Your loving wife,

J

PS Love me and think of me.

At 67 years old and again alone, Jennie accepted most of the invitations that came her way, including a trip to Rome, and then, fatefully, from Lady Frances Horner at Mells Manor near Frome, for many years now the home of the Asquith family.

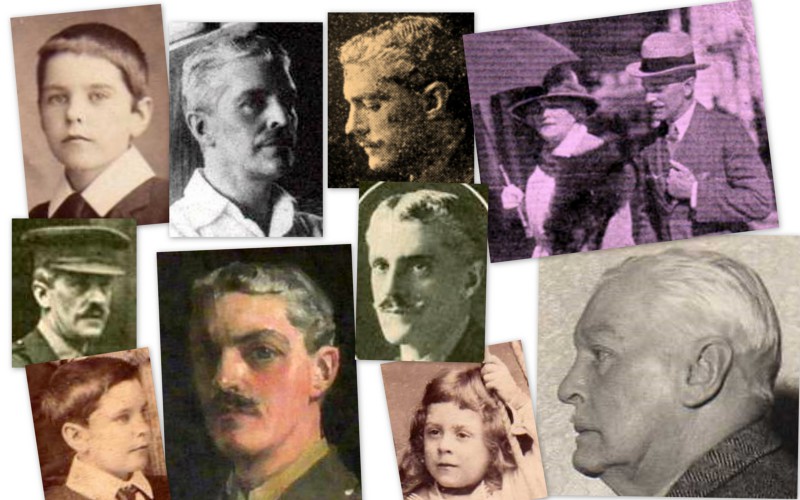

At teatime on Sunday 29 May, Jennie put on her new Italian shoes (had the maid remembered to sandpaper the slippery leather soles?) and hurried down the well-worn stairway.

Three steps from the landing she fell. Lady Horner heard her fall and cry out and propped her up with cushions. She telephoned for a doctor who came from Frome within a quarter of an hour and set two broken bones directly above the ankle, an ankle weakened years before by a fall on a grouse moor. There was very little displacement, but considerable swelling of the ankle and foot.

Two days later, Jennie was transferred in an ambulance with a doctor and nurse back to 8 Westbourne Street, where she made satisfactory progress. However, within two weeks, on 10 June, a portion of the skin blackened and gangrene set in. Winston summoned a surgeon, who was forced to amputate Jennie’s leg above the knee almost immediately.

Meanwhile in Africa, Montie, though distressed, is still not fully aware of the situation unfolding back in England. Business is going well for him and his newly formed London Coomassie [now Kumasi] Trading Company. He writes a letter which, in his turmoil, he dates 8 May — it should actually have been 8 June — two days before the leg was amputated, and in which he describes his distress and upset, and his promise to love her even more. He offers to return, despite admitting that his flourishing business would suffer if he did.

Five days later, upon receiving a telegram from Winston about the amputation and just before the next mail boat, he repeats his love for her, and adds that he is suffering all kinds of anguish, physical and otherwise, in sympathy with her and is seeking comfort from the Bishop of Accra. He finishes with “kisses for the poor little place where the stitches are”.

A further letter on 25 June is in much the same vein, despite a cable from Winston two days earlier, saying that the danger had passed. Montie repeats his reassurances about his business but reveals that he has mortgaged 8 Westbourne Street for more capital. He ends with more expressions of his love and devotion, but one cannot help feeling that Montie is under enormous pressure to prove his worth by providing for Jennie in material terms. Montie even encloses a map showing how the railway would run and help make his fortune.

Jennie knew how worried he must be, and sent a cable on 28 June saying she’d got his letters and was much comforted. She also added that she was all right and was sending him things, such as lavender water and toothpaste!

Back in London, the very next morning, 29 June, Jennie awakened feeling fine, but, after a good breakfast and without warning, the main artery in the thigh of the amputated leg haemorrhaged. Before the nurse could apply a tourniquet there was a heavy loss of blood and later that day she died. At the inquest on 1 July the coroner pronounced Jennie’s death as accidental, and she was buried the following day in the Churchill family plot of the cemetery at the quiet country church of Bladon, near Oxford. Montie was not to arrive back from the Gold Coast for another month.

Empty house

Finally back in England, Montie was greeted by an empty house and Jennie’s debts of £10,000, which he and Winston’s brother, Jack, had to deal with. To complicate matters, Jennie died intestate, since her last will had been made in 1915, before her final marriage, and was therefore invalid. Montie declined to inherit any of Jennie’s property of just under £40,000. Meanwhile, Winston was reported as spending his days weeping.

Montie’s two final actions in this chapter of his life were placing an acknowledgement in the Times for all the messages of sympathy he had received and a pilgrimage to Mells Manor, where, according to the Asquith family, Montie collapsed the moment he saw the stairs where Jennie had fallen.

Montie, clearly reeling, returns to the Gold Coast and his thriving business in Kumasi.

Marriage in Italy

All goes quiet for a few years and then, out of the blue on 1 July 1926 we find Montie, at the age of 49, in Perugia, Italy, marrying Donna Giulia Patrizi of Umbria, 11 years his junior.

Giulia, judging by the photo of her when she was 22, kindly provided by her great-nephew, Dottore Gianfranco Patrizi di Rasina, was a woman of great beauty, but there is no evidence of how the two met nor is anything known about their life in Umbria (it was, as Dottore Patrizi has described it, “tutta un mistero”).

Montie appears in the list of mourners at his mother Annie’s funeral in Glastonbury in 1932 and they return to England as a couple for Montie’s nephew Esmé’s wedding in 1933, but otherwise nothing is heard of him or them until suddenly this tribute appears in the Wells Journal on 25 November 1938:

DEATH OF MRS. MONTAGUE PORCH

HER CHARITABLE AND POLITICAL ACTIVITIES

The death occurred on Sunday, October 30th, at her home in the Upper Tiber Valley, Italy, of Donna Giulia Porch, better known as the Marchesa Giulia Patrizi. In 1926 she was married at Perugia to Mr. Montagu Porch.

Donna Giulia was the only daughter of the Marchese Patrizi della Rocca of Umbria and was noted for her beauty and her charm. As a result of her charitable and political activities she was held in high esteem. For many years she acted as secretary to her father when member of Parliament and Minister of Agriculture.

The obituary then described the hospital work Giulia had done both after the 1917 earthquake in Umbria and during the Great War, for which she was awarded medals, and her involvement with the Fascists in the early 1920s at the time of the famous march on Rome in October 1922 which resulted in attacks upon her and her homes by communists.

Clearly Giulia was not only beautiful but brave and strong-minded, and one of the many in those times who feared Communism above all else.

There is no mention of her age (she was just 50) or what she died of.

Donna Giulia was buried at the lovely Sanctuario della Madonna di Canoscio, 12 kilometres south of Citta di Castello near Trestina.

Giulia’s two homes in Citta di Castello and at Pietralunga still exist. The former is the residence of her great-nephew, the latter now a luxurious hotel called La Locanda del Borgo. The secondary school in Citta is named Istituto Superiore “Ugo Patrizi”, after her illustrious father.

Return to Glastonbury

The last sentence of the obituary states that he had a permanent home in Italy but it could not have been long before Montie, undoubtedly grieving and presumably seeing war clouds on the horizon, returned to England and to Glastonbury. There is an unsubstantiated report that he brought back with him an Italian manservant, who was interned as an alien, and for whom Montie got an exemption through an appeal to Winston, which the great man granted on condition that he not hear from Montie again for the rest of the war!

It is unclear just how much property Montie had in Glastonbury, but sometime around 1940, having lived on his own for a short time at the family home of Edgarley Lodge, he moved into a newly built house in Tor View Avenue, belonging to Hedley and Ethel Hucker, with whom he had become friendly.

Number 13 (as it was then, now 27) is not a spacious house and it must certainly have been a squeeze for Mr & Mrs Hucker and their three daughters, plus a 63-year-old man! So when number 12 next door (now 25) became available not long afterwards Montie bought it and moved in. In fact he was looked after just as well, courtesy of a passageway that was knocked through between the two houses.

There is some evidence that Montie still owned property in Italy after the war, since in June 1949 he writes home to Mrs Hucker, whom he addresses as “My dear Hostess”, from Trestina, just a kilometre from where Giulia is buried, and mentions a man called Pietro “working on the place”. Giulia’s great-nephew says that Montie inherited all her property, but given the haste with which he must have left in 1938 and the depressed state of postwar Italy, it is possible that he was obliged to dispose of a lot of it without delay and for a fraction of its value.

Confirmation of this third property came in a death notice which was recently discovered among papers belonging to Montie’s great-niece, Sally Melia, sent from Italy to his family by Montie informing them that Giulia had passed away at her property at Trestina after a short illness.

It seems that Montie brought little back from Italy, and did not keep a vast quantity of memorabilia from either marriage, although there is a story that some of his family papers and letters were destroyed when Edgarley Lodge was eventually sold.

A few items may still be in circulation. For example, it is said that Harry Carter, who used to live in Chilkwell Street, had a chaise-longue which he claimed had belonged to Jennie Churchill and which he had bought at a Cooper and Tanner sale of goods when one of the Porch family died.

Other less credible, but entertaining, stories exist. One of them goes that, because of the family connection, Winston would come in secret to stay at Edgarley Lodge during the war to escape for a day or two from the pressures of official life. This became known to German intelligence, and an elite Waffen SS unit was parachuted onto the Tor in an attempt to capture Churchill, and also to seize the Holy Grail for Himmler while they were in the neighbourhood. Unfortunately for them, their plan was discovered and an equally elite reception party awaited them. A firefight ensued in which the SS men were all killed. They were buried in secret on the moors and the whole matter was hushed up!

From Lodge to lodger

In 1948 the Huckers moved from Tor View Avenue and bought Abbot’s Leigh (better known now as Number 3) in Magdalene Street, and Montie moved with them.

Later on, their daughter Glenys (the late Mrs Phillips) and her husband George bought Abbey Grange close by and exchanged properties with her parents so that they could offer bed-and-breakfast at Abbot’s Leigh. Montie moved with them.

According to former neighbours, when the moves took place, furniture was pushed up and down the pavement, much to the amusement of the locals, who also found interest in the bedroom allocation at Abbey Grange and in Mrs Hucker’s hat-covered head, which was often on display to passers-by.

Mrs Hucker was dressy, always wearing one of her vast collection of glamorous hats, one of which is on show at her daughter Jill’s wedding to Roy Cleave in September 1953, and often a smart black coat. She bought the latest style and clearly enjoyed the attention it created.

Montie himself was well-groomed and took great care over his appearance, particularly his hair, which sometimes received the blue-rinse treatment. For all that, he had the reputation of being a kindly and charming, if reserved, old gentleman who was happy with the company of his friends the Huckers and the quiet, secure life they afforded him. He was very appreciative of their home and their cooking, and for this they would often receive the ultimate compliment in the still-austere early 50s with his phrase “Just like before the war!”

It is not surprising to know that even when Abbey Grange (and Abbot’s Leigh) became a billet for older Millfield pupils in the 1950s and 60s, the boarders saw virtually nothing of the elderly gentleman who occupied two first-floor rooms at the back of the house and enjoyed fine views of the garden, the Abbey grounds and the Tor.

In the papers

Montie shunned the limelight but he did not retire from public life completely. For example, he was listed in Jeffrey Wilson’s book as a sergeant in the Home Guard during the 1939–45 war, and later he was an active member of the Glastonbury Antiquarian Society; his signature occasionally appears in the minutes as one of the society’s vice-presidents. Also, having converted to Catholicism to marry Donna Giulia, he worshipped regularly at St Mary’s Roman Catholic Church in the town — just across the road from where he lived — and was a supporter of many local organizations and good causes.

News of him did reach the press, however, usually on the occasion of his birthday. The Evening Standard managed to catch up with him in 1959:

Returning from Italy just before the war, Mr Porch first lived by himself in Glastonbury [at Edgarley Lodge], and was a regular caller at Mr and Mrs Hucker’s fish and chip shop [sic]. One day Mrs Hucker noticed that his visits had inexplicably ceased and, calling round to his house, found him ill in bed. “So we invited him to stay with us,” said Mrs Hucker. “He is a wonderful gentleman.”

Every year he goes abroad for his holidays. This year he visited Rome and Sicily taking his friends the Huckers with him. Indeed my reporter tells me he is quite the most remarkable man for his age he has ever met.

(The reporter made an error: the Huckers did not own a fish-and-chip shop; it was a fishmonger’s shop, acquired in the 1930s, in Benedict Street. They bought the adjacent Mocha Berry coffeeshop in the 1950s, subsequently run by Glenys and her husband George Phillips.)

The following month, on 9 December, the same newspaper printed the photo of Montie in his living room with a short caption. Then it was the Daily Mail’s Vincent Mulchrone who managed to interview Montie for a full article on 21 December:

Mr Montague Porch’s favourite chair is so placed that when he looks across the skin of the leopard he shot in ’07 his gaze falls naturally on the portrait of the woman he loved, Sir Winston Churchill’s mother.

The story of the first meeting, the romance and the marriage has never been told, because the erect figure gazing at the oval portrait has never chosen to tell it. Until now. And even now he speaks carefully, the flood of memory checked now and again by a desire not to offend old friends or memories, to keep private those things which should be kept private. As he speaks, his voice never loses the tone of wonderment that she should ever have loved him at all: wonderment even that they should ever have met.

Just a few days later, another article illustrating Montie’s close relationship with his hosts appeared in a different national daily, when Montie is described as coming to the door of Abbey Grange and telling the reporter that he is spending Christmas at home with the Huckers to help look after his hostess who is in bed, sick with the flu:

Mr Porch is an active man and spends much of his time in the garden or working at business papers. Most mornings he takes a stroll around the town’s shopping centre. Every summer he and Mrs Hucker take a month’s holiday together. Last year they borrowed Mr Hucker’s Jaguar to tour North Wales.

“They’ve been all over the world together,” said 62-year-old Mr Hucker. “It was Italy a couple of years ago, Turkey before that. As soon as Christmas is over they’ll be making their plans for next year. I don’t mind not going with them. In business you just can’t do that sort of thing. Somebody has to stay behind to look after the shop.”

A brief item appeared on the day of Montie’s 84th birthday in 1961, wishing him well, and a fuller one in March 1964, which was to be Montie’s last appearance in public, so to speak, for he passed away peacefully at home nine months later, on Sunday 8 November 1964.

Glastonbury’s last Porches

The 1960s were a sad decade for those members of the Porch family who had remained in Glastonbury, with the deaths of both of Montie’s surviving sisters, Jessie and Queenie, and his cousin Dorothy. [See family tree]

A member of the younger generation too passed away — Montie’s second cousin Robin Porch of Southfield, who was the grandson of Albert, the last Squire of Edgarley, a popular figure in the community and the only Porch from Albert’s immediate family to have returned after the tragic events which saw them leave Edgarley at the beginning of the century.

The press reported on Montie’s will early the following year, informing readers that the charcoal portrait of Jennie by John Singer Sargent so dear to Montie was left to Winston. It would have been with Winston for precious little time before his own death in January 1965, when it was passed on to Randolph and thence to his son, Winston, who died in March 2010. The original is now with Winston’s great-grandson, Randolph.

Otherwise, in Montie’s will, after a few particular legacies, including £2,000 and his house in Tor View Avenue to Ethel Hucker, the £50,000 remaining in his estate was left to members of his nephew Esmé’s family.

Montie’s funeral, which included a full requiem Mass at St Mary’s conducted by Father Sean McNamara, took place on Wednesday 11 November and was followed by Montie’s interment in Glastonbury cemetery, in the Porch family plot, though curiously and rather sadly, in a grave without a headstone.

Montie’s destiny

So what can we make of Montie and his “charmed” life, 50 years on?

On the surface of it here is a man to be envied — born into a wealthy, provincial, land-owning family, who enjoyed a private education, and connections which opened the door to adventure and service, not all of it without danger. A man of cultivated taste and enquiring mind, an archaeologist, an able administrator and businessman. A man nevertheless of some contradictions — a generally quiet, undemonstrative man, though clearly capable of impatience and forcefulness when under pressure, an essentially private man, though one willing to dice with fame in return for love and approval; a man perhaps continually seeking a role and a place in the world, but who never quite finds it.

Let us look at the facts. Born to the second son of the Squire of Edgarley into a family stretched between India and England, with his mother and father moving from one country to the other as children are conceived, born and left in the care of an older generation, Montie is unlikely to have had any kind of relationship with his father who dies in Bengal when Montie is just 9.

The next 20 years become interrupted and nomadic — Bath, Oxford, South Africa, Oxford again, Egypt, Nigeria, with frequent returns to England, Weston-super-Mare rather more than Glastonbury. There is an emerging pattern of searching, not settling, the lot perhaps of the second son of a second son in those times.

Then suddenly the coup de foudre, as fate introduces him to the most dazzling star in the universe. He is drawn irresistibly into her world, where his search for love and identity comes to a temporary end, only for him to realize that he remains an outsider, destined to live suspended between his privileged but quiet rural roots and the dizzy circles of fame and high society.

Fate then delivers him another telling blow, a blow which even prevents him from standing at his dead wife’s graveside with his new-found family. And so Montie not only loses his beloved but also, along with her, his own identity, becoming known to most on these shores as little more than “the man who married Jennie Churchill”.

It is hardly surprising, then, that Montie returns to Africa to build another future for himself.

Does the Gold Coast end his search? It seems not, for suddenly, a few short years later, we see another future open up for him, this time in Italy. Sadly, he is not destined to belong to this one either.

Then the final return to England, where Glastonbury and the Huckers now become his family and his world, a safe, comfortable world, a world he previously tried to climb clear of but one which almost inevitably draws him back.

Montie’s later life is not without its purpose and its joys, but it is one without the blessing of children, without a home of his own — any more at his death than at his birth — or the pride of a distinguished career to look back on.

So was his a charmed life or was he something of a lost soul?

Whatever the truth of it, one feels that this reserved but resilient man could not escape treading an inevitable path back to Glastonbury — even to an unmarked grave.

Author’s note

The book’s title was originally Monty Porch: a charmed life, but this new edition uses the spelling Montie throughout. Having recently had access to a further quantity of Montie’s personal papers, the author acknowledges his previous -y spelling to be incorrect, though it is common in newspapers and other sources. The undoubted preference of the man himself and the family is “Montie”.

Otherwise this edition has comparatively minor revisions. Several photos are improved; the one from the Durbar race at Zaria and the one at Glastonbury cemetery were not in the first edition.