Montie Porch:

a charmed life

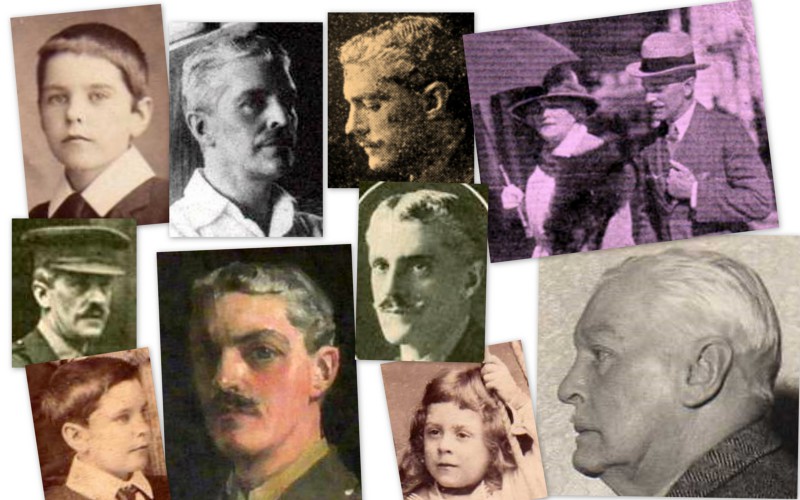

The Glastonbury man who married Winston Churchill’s mother

by Roger Parsons

Copyright ©2012, 2019 by Roger Parsons. Published in print and web form by Abbey Press Glastonbury.A life of contrasts

Montie Porch — born into the family of landed gentry, Oxford, volunteer in the Boer War, adventurer, archaeologist, artist, an administrator in the Colonial Service and a soldier in the military in Africa before and during the First World War, husband of the most famous and glamorous woman of her time, then of the daughter of an Italian aristocrat, a fortuitous refugee from pre-war Italy; and an elderly gentleman living quietly, until a peaceful death at the ripe old age of 87, in the town of his birth.

This is clearly a life of extraordinary contrasts, a life lived to the full in momentous times and, in some part, among the great and the good. Some have described Montie’s as a charmed life. It would seem so.

Over the course of this short biography we shall try to unravel some of the mystery that is Montie, to reveal the man behind a rather secretive veneer, who shunned the limelight but who was once irresistibly drawn to it for ever through his love for a woman nearly 30 years his senior.

Sources

It is no surprise that the information about Montie’s life for the few brief years of his famous marriage is plentiful, but, on the whole, quite scarce for the rest. Indeed, readers who have accessed the excellent article on Montie on the Churchill Centre website and the relevant sections in the biographies of Jennie Churchill may be disappointed not to discover much that is new in what follows. It is also quite possible that there are some who knew Montie himself and could add more to his story. Therefore, apologies are offered for any aspects of this biography that may be considered inaccurate or inadequate.

As already stated, Montie’s life is, obviously, explored to a greater or lesser degree in the many biographies of the Churchill family and of Jennie in particular, most notably, in the two-volume Lady Randolph Churchill by Ralph G. Martin, which draws on quotes from an interview with Montie himself that appeared in the press in 1959, and from details contained in the Oswald Frewen Papers.

Other biographies and sources used are listed in the Acknowledgements, together with the names of those who have generously contributed to the biography in different ways.

Early years

Montagu (occasionally with a final e) Phippen Porch was born on 15 March 1877 at the Abbey House in Glastonbury, the third child of Reginald and Anne Porch.

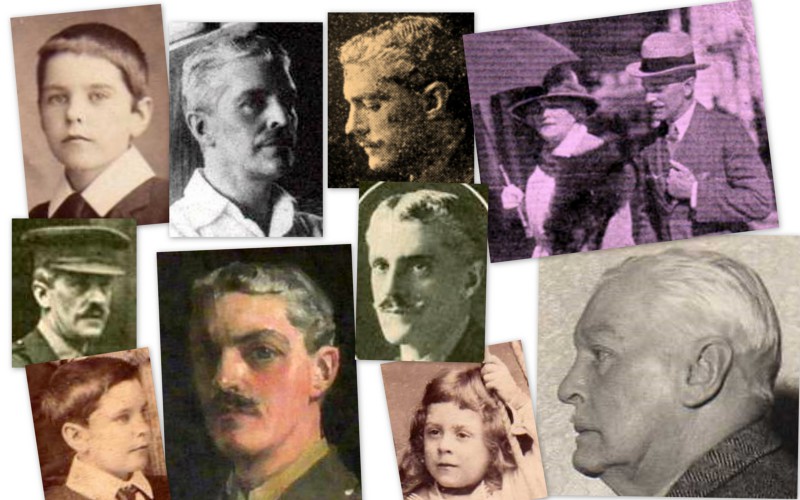

Reginald was the second son of Thomas Porch Porch (see family tree) and therefore younger brother of John Albert Porch, the last “Squire of Edgarley”.

Anne, who was born in Geelong, Australia, was the daughter of James Austin, several times Mayor of Glastonbury, and the then owner of the Abbey and the Abbey House. James was one of the many Austins who had made their fortune in Tasmania and Victoria, but he was one of the few who came home to flaunt their influence and wealth, and spend it on such things as the Abbey!

In the photo of the wedding party of Reginald and Annie, as she was known, outside the Abbey House in 1870, stands Reginald’s father Thomas Porch Porch on the far left, with Reginald’s elder brother, Albert, next towards the centre. Annie’s father, the white-haired James Austin, is just behind her on her left.

The first photo of Montie, aged about 4, must have been taken around the time of the 1881 census when he is recorded as living at the Abbey House with his maternal grandparents, James and Rebecca Austin.

By then, three children had been born to Annie and Reginald, the eldest, Austin, in Bengal.

Besides Montie and his brother, the 1881 census lists two girls, Jessie, 9, born in Glastonbury, and baby Ethelind (better known as Queenie), who was born in Weston-super-Mare. Yet to arrive is Montie’s youngest sister, Winifred, born the following year in India.

If Montie’s parents were not on the 1881 census, where were they? Well, doubtless in India, where Reginald had been a civil servant since 1861 and where Annie was pregnant with Winnie. It is quite possible that the photo of Montie in sailor outfit was taken to send to Reginald so that he could see his son for the first time.

Immediate family

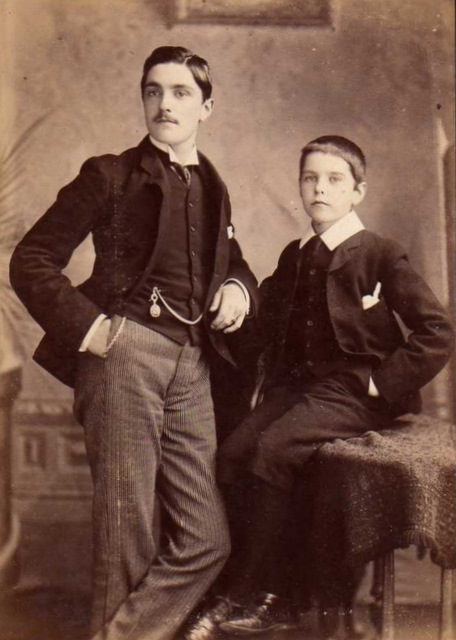

Austin, who was educated at St Peter’s in Weston-super-Mare, Clifton College and Corpus Christi College, Cambridge, where he matriculated in 1889, became a private tutor and breeder of Great Danes. He married Eileen Greenslade in 1897 but the marriage was destined not to last because of his homosexuality, although there was a son Esmé, who became a professional soldier with the East Surreys, a regiment in which several other Porches served, and a daughter, Bryda. Of Esmé’s two marriages, the first was a very favourable one to the Burma Oil heiress Vivian Finlay, the prolific romantic novelist who wrote mainly under the names Alex or Vivian Stuart, who bore him two daughters, Gillian and Jennifer. From his second marriage, Esmé inherited a son and a daughter. His sister, Bryda, also married twice, and had one daughter, Sally, from the first marriage.

As for Montie’s sisters, the eldest, Jessie, never married despite being presented at court by Mrs Patrick Campbell. She lived at Edgarley Lodge from 1927 for some years, also in Magdalene Street, then at Southfield in Bere Lane, becoming known as one of the two elderly Porch spinsters residing there — Dorothy Porch, a cousin, was the other. Eventually Jessie had to move to Mount Avalon, at that time a residential care home on Windmill Hill, where she died in 1966.

Ethelind, or Queenie, married Edward Gillmore, an architect and well-known local rugby player and cricketer from Weston-super-Mare, in 1905. They went to live in Paddington for a time, but eventually divorced. Queenie then married a Reginald Horton in 1935 at St Audries, West Quantoxhead, where she died, childless, in 1967, at the age of 87.

Winifred (“Winnie”), the youngest of Reginald and Annie’s children, was born in India in 1882. She never married and lived in Glastonbury for most of her life, including at Edgarley Lodge from 1927, and at the red-brick Elton Cottages, near Edgarley. However, we know from a letter Montie wrote in 1957 that Winnie was a patient at Bailbrooke Mental Hospital near Bath, where in fact she died just a year later, aged 76.

One other relation who seems to have been a mainly lifelong Glastonbury resident, was Montie’s cousin, Dorothy, the only child of his uncle Arthur and aunt Elizabeth. Dorothy, who never married, lived at Southfield from 1932 until her death in 1967. She trained as a nurse and was in the Women’s Royal Naval Service in the First World War, but was better known in Glastonbury as the owner of a stubborn Pyrenean Mountain dog and as a woman who possessed the unusual ability, for that time, to decarbonize her own car, a Hillman 80!

The absent father

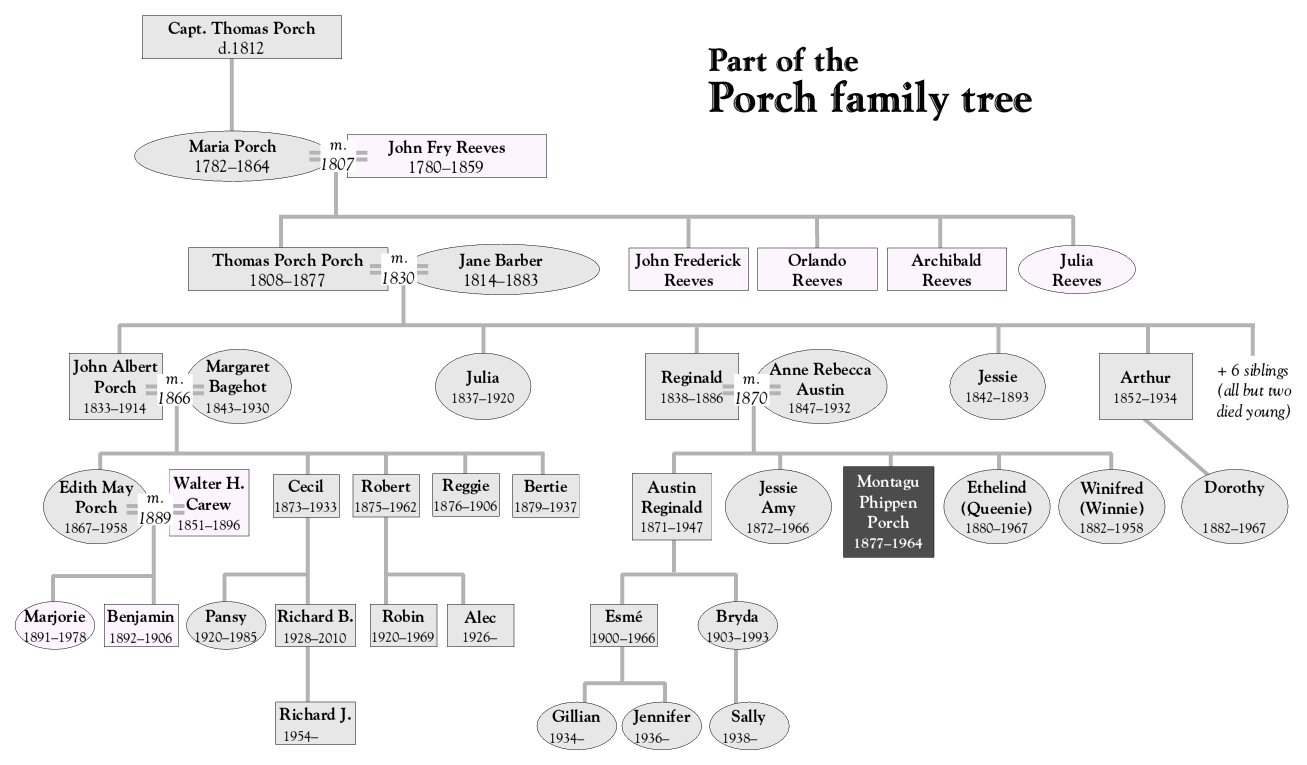

The first family photo to have come to light, taken around 1888 when Montie was about 10 and Austin 18, is significant for the absence of one particular member. As it is, we have Jessie at the back, rather statuesque, Queenie on the right, with a bit of a twinkle in her eye, and, on the left, dear Winnie, looking wistfully beyond the camera.

One might, at first glance, assume that Reginald was continuing to carry out his colonial duties in India. Sadly, no; her dress and the look on poor Annie’s face tell all — that there was no longer a head of the family, for Reginald had died of fever at Poona in June 1886.

A lovely stained-glass window, located just above the font where Montie was almost certainly baptized, was put up by Annie in memory of her husband in the south transept of St Benedict’s Church, Glastonbury.

Annie continued to bring up her children without the help of a second husband and seemed to remain close to them. She lived in Weston-super-Mare until 1925, when she moved back to Edgarley Lodge to be looked after by her two unmarried daughters, Jessie and Winnie, until her death early in 1932 at the age of 75. Her obituary in the local paper states, rather sadly, that she was an invalid for most of the seven years she was back in Glastonbury and, having spent long periods abroad, was “not well known to the current generation”.

School and Oxford

In 1891, five years or so after his father’s death, the census has Montie, at the age of 14, living in Bath and attending Bath College for Boys, which was originally situated in Bathwick at the old Sydney Hotel (now the Holburne Museum). The school was founded in 1878, but clearly did not flourish, closing before the end of the century.

As for the rest of the family, which now included Montie’s youngest sister Winnie, aged 9, the census records them as living at 4 South Road, Weston-super-Mare, in a property known as Bancoorah House — so named in memory of Reginald after the town and district (now Bankura) in Bengal for which he had responsibility. Bancoorah House is now incorporated into Addington House, Madeira Road.

After Bath College for Boys, Montie progressed to Madgalen College, Oxford, as a “commoner”, or student without a scholarship or exhibition, spending three or four interrupted years there, 1897–99 and 1901–02.

One might assume that Montie was not unhappy to be away from Glastonbury around this time, given that 1897 was the year, so catastrophic for the wider Porch family, that his cousin, Edith, Squire Albert’s only daughter, was found guilty of murdering her husband — a crime that effectively put an end to the Edgarley Porches’ peerless reputation and influence in this part of the world. (The poisoning case, which took place in Japan, is covered in full in my companion booklet Victorian Edgarley: the fall of the House of Porch.)

The Boer War

As the Madgalen College archives do not show what he read, we must assume that Montie studied for a Pass degree, which was less demanding than an Honours. This was just as well, perhaps, since he obtained a special dispensation to break off his studies in 1900 to serve in the Boer War, enlisting in the February, at the age of 22 years 10 months, as a Trooper (Private) in the 47th Company, 13th Battalion of the Duke of Cambridge’s Own Special Corps of Imperial Yeomanry (nicknamed the “Millionaires’ Own” because of the number of hugely wealthy men in its ranks!).

Montie’s medical examination states that he was 5 feet 7 inches tall and weighed 138 pounds, and that he had dark blue eyes, black hair and a scar over his left eye.

Montie’s 188 days of service in Transvaal and the Orange Free State were undoubtedly far less glorious than that of two of Squire Albert’s sons, his cousins Bertie and Cecil, in particular the latter, who was welcomed back to Glastonbury as a hero after being wounded at the battle of Spion Kop. Indeed it is almost certain that Montie was involved in one of the major reverses of the whole war: in May 1900, the 13th Battalion under Lt Col Spragge, having allowed themselves to be lured into a trap, surrendered near Lindley following a battle at Yeomanry Hills, a surrender when relief was but minutes away.

The 500 prisoners, of whom Montie was doubtless one, were released a few months later when British forces captured Pretoria, but the loss of this elite battalion of landed gentry caused a national outcry in England and resulted in an Imperial Commission into what became known as the “Lindley Affair”.

Montie, having been awarded a Queen’s Medal and three clasps, returned to Oxford to complete his studies, receiving his BA in 1902 and his MA in 1904.

Archaeology in Sinai

Montie may well have studied and developed a love of archaeology at Oxford, since local newspapers in Weston-super-Mare in 1903 report on his donation to Weston Museum of flint chips he had discovered in the Hutton and Banwell Hills, and their display in glass cabinets.

This interest took him much further afield in the winter of 1904–05, when we find Montie in the Sinai peninsula with the eminent archaeologist Professor Flinders Petrie and his Egyptian Exploration Fund, exploring the area to which the ancient Egyptians had gone to mine turquoise. Margaret Drower in her book A Life in Archaeology describes how “Montague Porch, a gentleman of independent means, who was anxious to add to his collection of palaeolithic flints, asked to accompany the expedition for part of the time.”

Early in December 1904 Montie and his Italian manservant joined the party at Wadi-el-Maghara (Valley of the Caves) and they set up an enclosure with tents. They needed to be on guard, for the local Bedouin had a reputation for being untrustworthy and uncooperative. True to form, they not only refused to disclose the whereabouts of the nearest well (Petrie eventually found one, much to the Bedouin’s wonderment, by simply keeping his eye on a lone camel walking in the direction of the well!) but also stole stores. In fact one day Montie’s manservant, Lorenzo, caught two of the thieves in a trap, although unfortunately they escaped before the others in the party could respond to Montie’s gunshots.

Two days after this incident Montie left the expedition to look for palaeolithics in the Nile Valley.

In 1905 Montie gave a paper to the Somerset Archaeological & Natural History Society about the expedition, and in Flinders Petrie’s own report, Researches in Sinai, he describes Montie as the “discoverer of a well-marked flake of flint at 15ft. deep in an old filling of Wady Meghara”.

The flint that Petrie mentions may be one of the three which made their way, in the first instance, to the Weston-super-Mare Museum and then many years later, in 1960, to the Flinders Petrie Museum at University College London, where they still are.

Montie’s search for flints in Sinai was not to the exclusion of all else, as testified by a small sketchbook of his, now in the possession of the Hucker family in Glastonbury. In it are some delightful miniature watercolours of desert landscapes, plus others of rural and hunting scenes from the southwest of England, painted either from memory in Egypt or upon his return.

In view of all this it is entirely likely that Montie was acquainted with the Abbey archaeologist Frederick Bligh Bond, who, coincidentally like Montie’s sister, Winnie, lived for a short while at Elton Cottages in Coursing Batch, Glastonbury, and, like Montie himself much later, at Abbot’s Leigh, adjacent to the Abbey ruins. Additionally, Bond’s family lived very near the Porch home in Weston-super-Mare, and Bond had attended St Peter’s School in Weston as Austin had, and Bath College, like Montie.

West Africa

His studies at Oxford and adventures in Sinai over, it was time for young Montie to find a career for himself. It was Africa that called him back — this time the west rather than the northeast — proving the old colonial maxim that it was to this continent that second sons went to further themselves, while first sons went to India.

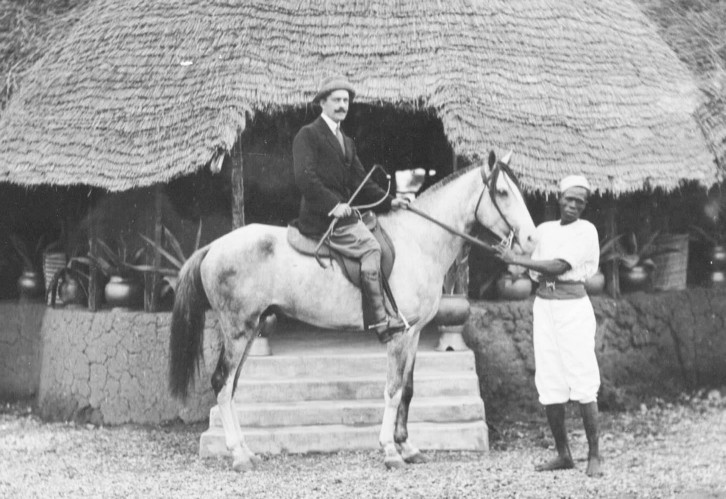

So in 1906, when his future stepson, Winston Churchill, was Under Secretary of State for the Colonies, Montie applied to join the Colonial Service. Interviewed by Sir Edward Marsh, Churchill’s private secretary, he was assigned to Nigeria as a Third-Class Resident. Later Montie was quoted as saying, in typically unassuming fashion, that he remembered Marsh asking him if he rode and that because he was able to reply he had — with the Taunton Vale Foxhounds — he was given a job in Northern Nigeria! (There were four grades of Administrative Officer in the African Colonial Service — First, Second, Third Class and Assistant Residents.)

In 1907 Montie was placed in charge of the division at the town of Jema’an Daroro in Nassarawa province (now part of Plateau state) serving under four successive Residents who were stationed at the provincial headquarters in Keffi, 500 miles northeast of Lagos.

Northern Nigeria was not at all an easy posting. Sir Percy Girouard, the then Governor, described the region as “backward and unsatisfactory”, and was very uncomplimentary about its main tribe, the Kagoro.

It is not surprising, therefore, that Montie, who had been told to collect “tribute”, did so with some difficulty. In fact on several expeditions his detachment was fired upon, and on one occasion there were several casualties, including one death, among his men.

After an investigation of these events, Montie was, rather harshly perhaps, held responsible by the Resident and was relieved of his post. However, the following year he was given a reprieve by the Governor and allowed to return to Nigeria, this time to the provincial office in Zaria, a town 500 miles northeast of Lagos, which today has half a million inhabitants.

Montie was never again entrusted with the charge of a division, but he seems to have done well, particularly at road-making. In later life he claimed to have built the first town of Kaduna, the settlement created for the construction of the railway line. This was certainly a time of opportunity and growth for Nigeria, and Montie’s efforts would have been instrumental in the development of trade.

In this long, settled period from 1908 to 1914, Montie built for himself a large, impressive house in traditional Northern Nigerian style, near the Emir’s palace in the centre of Zaria City.

Jennie

His time in Nigeria is crucial to the next step of Montie’s life since it is there that he becomes the friend of Hugh Frewen, Assistant Resident in Northern Nigeria, and Private Secretary to the Governor. Hugh was the son of Moreton and Clara Frewen (née Jerome), the sister of Jennie Churchill, and it is in 1914, at Hugh’s wedding in Rome to the daughter of an Italian duke, that Montie and Jennie meet.

Anita Leslie writes that Jennie was attracted to Montie in various ways: the eerie feeling she had for ancient Egypt where Montie had gone with Petrie, and the admiration she had for men who had volunteered to fight in the Boer War. She also records that Hugh’s was a mixed marriage — a rarity then — and that, “when the Roman Catholic priest delivered more a scolding than a blessing, Montie’s humorous black eyes met Jennie’s in amusement”.

A piano footnote

By strange coincidence, a Bechstein grand piano, recently donated, has found its way to St Benedict’s Church in Glastonbury, where it now has a home in the south transept — just under the stained-glass window set up by Annie Porch in memory of Montie’s father, Reginald.

The coincidence is that the piano began its life at Blenheim Palace, home of the Churchills. It is therefore perfectly possible, and intriguing to consider, that Jennie and Montie, who both played the piano, might have spent time making music on this splendid instrument.

At the wedding party, Montie asked her to dance, but Jennie smiled and suggested that he go and dance with some of the younger girls. Montie was then 37, three years younger than Winston.

They met at lunch the following day and then several times over the next fortnight, visiting monuments and discovering a shared love of music. Both played the piano. Their friendship deepened to the point where Jennie felt able to comment on the snow-whiteness of his hair, and shortly afterwards she described in a letter to her sister, Leonie Leslie (the third of the Jerome sisters), how she had met a young man she would probably marry.

The Great War

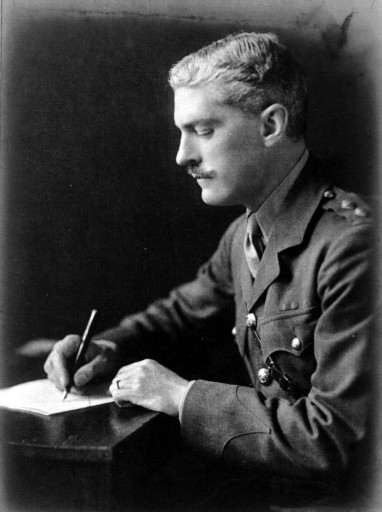

Back in Nigeria that same year, Montie is soon involved in military activity. The German authorities in the Cameroons had sent troops into the southeastern extremity of Northern Nigeria, and a company was sent to drive them out. Montie accompanied the column as Intelligence Officer, attached to the Nigeria Regiment, with the rank of Temporary Lieutenant, and was well reported on by the commanding officer.

Letters between Jennie and Montie started to flow in both directions. Montie’s brimmed with a mix of information and restrained emotion.

His first, written on the boat which had taken him to Nigeria, describes the aspirations he held for his country, and for her friendship and approval. He also writes about the young soldier servant and the dog he has taken with him — a Great Dane, perhaps one of the pedigrees bred by his brother Austin at his home “Dane End”, in Northwood, Middlesex.

In other letters, in October 1914, he describes the difficult conditions in the fighting against the Germans:

Your dear letter written on the eve of “Armageddon” finds your humble friend at the front beating back the attacks of the covetous Hun.

Lots of scrapping we had & I lost some gallant comrades. As yet our campaign has received little recognition — far greater dangers than trench work have been endured by our men who winter and summer have braved swamp and jungle, fever and bush ambuscades, heavy marches & fighting in terrible heat. Tormented by insects, stung by all the creatures of the bush, scorched by un-shaded sun in the fiercest heat of an African summer — such has been our lot.

In a letter dated 2 October 1915 he tells of his return to Zaria as Resident and his task of collecting taxes from tribes who had been emboldened upon learning that “all white men of consequence” had gone off to the Great War.

Three weeks later he is about to return by boat to the UK:

I am 5 months overdue for leave and sail on October 26th. I shall go straight to Kewstoke Somerset, where a patient old housekeeper & a man await me in a roomy cottage poised on a spur of the Mendip which dips into the Bristol Channel. I dread the first few days in Somt. Relations to be visited & tenants seen. I shall hie me to town. I shall live at the United Empire Club quite near you but won’t be a nuisance. I’ll only come when I’m called. Edgarley Lodge my little place near Glastonbury has just been let on a seven years’ lease! — Thank goodness.

Montie is not unaware of the horrors unfolding in Europe, not least because of deaths in Jennie’s family, and writes in the same letter of late October 1915:

Ohimè [“Oh dear” in Italian], this horrible sickening war, will it ever end. Almost all the men one has ever heard of seem to be either killed or wounded. Poor Lady Leslie, I heard of her loss. All my men kith & kin are in the trenches save brother-in-law Gillmore who is with his regiment in India.

It is well for you that you have lots to do, dear friend, you will then have less time for grief and heartache. I am indeed glad you are running the American hospital. History repeats itself. Jan: 15 years ago, I, a trooper coming of age on my way to the front, passed a gorgeously equipped American hospital run by one of the most brilliant & beautiful women in England. Now you are again taking your part in this bigger & more frightful war.

I too have played my small part all they would let me do.

Au revoir, dear Lady Randolph,

Your devoted friend

M.P.

The hospital ship Montie refers to is the converted cattle transport — the Maine — which Jennie had famously kitted out in 1900 to care for the wounded of both sides in the Boer War. Montie may be stretching the facts a little here — to encourage a hoped-for shared destiny perhaps — since the Maine, with Jennie aboard, had already arrived in South Africa in January 1900 whereas Montie’s troop ship did not reach Cape Town until late February, when the Maine was berthed in Durban.

In June 1916 Montie is back as Resident in Zaria in bullish mood, describing the three railways in his Province and his confidence that Kaduna would become the future capital of Nigeria.

On his next leave in November 1916 he meets Jennie again. By then he had fallen in love.

At this point Ralph Martin writes:

Montagu Porch resembled George Cornwallis-West [Jennie’s second husband, whom she had divorced in 1914] only in that they were both very handsome. But Montie was a much less forceful man, and he did not have George’s aggressive gallantry with women. His background was that of a country squire in Glastonbury. His neighbours there described him as “nature’s own gentlemen”, “a quiet man and a kind man”, “a man of oldfashioned courtesy”. “You never knew what he was really thinking and he seldom told you...” “...At a meeting he would always agree with the majority.”

A close friend was later quoted as saying “He was a very dapper man — the kind of man you would expect to wear spats, though he never did.”