Victorian Edgarley

The fall of the House of Porch

by Roger Parsons

Copyright ©2010, 2014 by Roger Parsons. Published in print and web form by Abbey Press Glastonbury.

Setting the scene

Edgarley Hall, at the southern foot of Glastonbury Tor, has been the home of Millfield Preparatory School since 1945. For probably almost 200 years from the early 18th to the early 20th century, it was the home of a remarkable family whose sudden fall from grace, primarily at the hands of the only daughter of the last squire, stunned the local community and the wider world. This and two further sad events shook the family to its core, and ensured that in May 1914, when the last squire died, the house and estate were left to his children, who sold up and never returned.

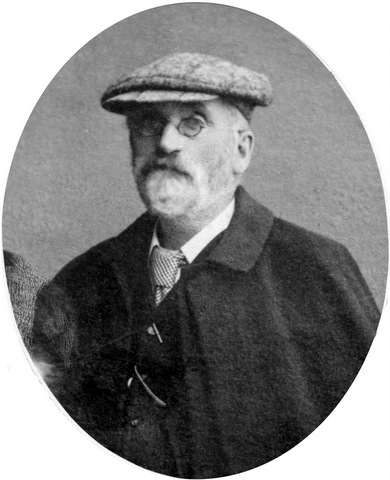

The last squire was John Albert Porch, known as Albert Porch, an apparently popular and kindly gentleman, who graced public life in Glastonbury for many years. This obituary lies strangely hidden away on page 8 of the Somerset and West of England Advertiser of 5th June 1914.

Death of Mr J. A. Porch

Mr J. A. Porch, a former alderman of the borough and three times mayor of Glastonbury, died on Wednesday last week at his residence, Edgarley House, after a brief illness. The deceased gentleman, who had attained the ripe age of 81 years, was a member of a well-known Glastonbury family, at one time owners of the Abbey House and ruins. He was born there in 1833 and spent practically all his life in Glastonbury.

He took a keen interest in the affairs of his native town and served continually on the council from 1871 to 1901, when, owing to increasing deafness, he retired. He was raised to the aldermanic bench in 1882 and was three times Mayor — in 1879, 1882 and 1897. In political life Mr Porch was a liberal, but his disapproval of the Home Rule policy of Mr Gladstone forced him to join the ranks of the Liberal Unionists.

He was a churchman and for many years Churchwarden of St John’s, his last tenure of office being 1900, when he retired. His funeral took place on Saturday.

This is a very matter-of-fact account for the head of one of Glastonbury’s most active, wealthy and widely respected families, which had provided the community with mayors, aldermen, JPs and general benefactors over a long period of time.

In the account which follows, we will try to make sense of this story, a story in which fate, or possibly something more sinister, seems to have played a key role, snatching the golden spoon in Albert’s hand away so suddenly, catastrophically and undeservedly that this large and influential family, within little more that 30 years of its height in the 1880s, disappears without trace in a manner that could be considered Hardyesque.

The beginning

Let us begin the story with a leather-bound book in possession of the Porch family called Glaston Charters, compiled by Thomas Porch Porch (more of him later) which contains a copy of the charter granted to Glastonbury by Queen Anne in 1705. A William Porch (“our well-beloved”, as Queen Anne described him), appears in it as one of the Burgesses, or leading citizens, of the town.

Whether William Porch owned Edgarley (originally one of the granges of the Abbey) has not been established, but what is clear is that by the end of the 18th century the Porch family was firmly established in the Glastonbury and Wells area and had done very well for itself from the wool industry. A Captain Thomas Porch had a wool factory in Wells and a large house on the Cathedral Green. His business was then described as “wool staplers”, an antiquated expression meaning a dealer in wool. The Wells Porches were wealthy enough to have a family vault in the cathedral.

Captain Thomas Porch also owned the Edgarley estate, having bought it sometime in the middle of the 18th century. We know little of the house of that time, although Burke in his Commoners of Great Britain of 1815 wrote: “There stood a hall of great antiquity known as St Dunstan’s Hall, but Mr Porch, unconscious of so valuable a relic, gave orders for its destruction, which were too fatally carried into effect.” It is very possible that the oak beams in the reception area of Millfield Prep School were from that same St Dunstan’s Hall, and of course the bricked-up barrel-vaulted passageway or carriageway seen from outside is likely to have been a feature of the Georgian house, whose solid rectangular proportions were somewhat hidden in the changes of the late 19th century, which we shall come to later.

Captain Thomas Porch was a Justice of the Peace for the county and a captain in the Militia. He courted a Julia Woodward, whose brother Colonel Woodward was sometime Lord Lieutenant of Ireland. However, her extravagance put him off marrying her, although the relationship did produce a daughter, Maria, in 1782.

Maria Porch: a mind of her own

There were plans for Maria to marry her handsome cousin, Thomas’s profligate nephew Captain John Elliott Porch of the First Regiment of Foot Guards (later the Grenadiers), but her father old Captain Thomas Porch had the engagement broken off after Captain John had apparently gambled away a huge sum of money in a single night to the Prince Regent. Thomas was understandably unwilling to see her inheritance go the same way!

In his book Stuckey’s Bank, P. T. Saunders says this was contemporary with Maria’s first meeting with a young solicitor, John Fry Reeves, who came from a Nonconformist family, originally from Bristol (with links to the prosperous Fry family) but now lawyers and bankers, and landowners at Hartlake, between Glastonbury and Wells.

In Maria we may see the first signs of typically independent-minded Porch women. According to Saunders, Maria, described as attractive, intelligent, a good horsewoman and from a wealthy family, came across John Fry Reeves as she was out riding on the Glastonbury road to Wells, took an instant liking to him and there and then decided that he was the one for her.

Conventions of the time did not allow her to approach an unknown young man and talk to him, so on another ride a few weeks later, she surreptitiously loosened her stirrup leathers and slipped from her horse, giving the young man a chance to “rescue” her. Like other Porch girls after her, she had made her way to the man of her choice, and they married in 1807. With his wife’s wealth and local connections, Reeves was able to acquire a bank at Glastonbury, which flourished sufficiently for him to open a branch in Wells in 1820 and another in Shepton Mallet the following year.

Saunders also tells us a story in the family that serves to illustrate what a quick-witted and resourceful woman Maria was. Faced with a run on the bank when ready funds were temporarily scarce, she ordered the servants to take sacks to the Tor, fill them with sand and return them so that she could place a single, visible layer of gold sovereigns on the top, to convince doubters that all was well!

All must have been well, since Armynell Goodall, in her book on the Bulleids, reports that sometime in the first two decades of the 19th century John Fry Reeves had mortgages on a third of all properties in Glastonbury.

Thomas Porch Porch

John and Maria’s first child Thomas Porch Reeves was born in 1808. Thomas was sent to Charterhouse, where he proved to be a sound classical scholar, and continued his education at Trinity College, Cambridge, at about which time his father bought the Abbey estate, probably with a combination of Maria’s money and that which her father, old Thomas Porch, had left to his grandson. He left not only money to his grandson but also the Edgarley estate, provided that, on reaching the age of majority, he change his name to Porch. He did this by a legal process called “sign-manual” — thus becoming Thomas Porch Porch!

At this stage we see the emergence of a double heraldic crest, where the eagle, from the Reeves side of the family, faces the wolf, from the Porch side. In the full coat of arms the Reeves quarters feature the “Pelican in her Piety”, that most Christian of symbols of self-sacrifice in which the Pelican vulns, or wounds, herself in order to feed her young. This symbol can be seen in such distant places as Cologne Cathedral, or nearer at hand on Sharpham House, on St Michael’s Tower on the Tor, on the exterior walls of Edgarley House, and on the gateway of the Abbey House, which John Fry Reeves had built between 1825 and 1830.

Despite the union of Porch and Reeves on the coat of arms, it is perfectly possible that Thomas’s change of name, allied to his inheriting the Edgarley estate, caused feelings of animosity between the two families to take root, feelings which were to surface in a dramatic way twenty or so years later.

It was at the Abbey House that Thomas began his married life in 1830, having wedded Jane Barber, the daughter of Edward Barber of Barston Hall, Warwickshire, on her 16th birthday.

Having been steeped in the Classics at Cambridge, Thomas was deeply interested in antiquities of all sorts and combined this with his love of poetry in a work of considerable size and erudition called The Mysteries of Time, or Banwell Cave, a poem in six cantos, which was published and ran to a second edition in 1833, although few would wade their way through it today.

Banwell Caves, a Site of Special Scientific Interest and open to the public several times a year, comprise, inter alia, “a Bone Cave” and “a Stalactite Cave”, which lie within the grounds of a large house, at the western end of Banwell Hill. The caves contain barite deposits, a mineral found in greater abundance and variety here than at any other place in the Mendip Hills, and are used as a hibernation site by greater horseshoe bats. There are also several grottoes and follies, including Banwell Tower, which was completed in 1840. The caves are occasionally open to the public.

One could safely surmise that sometime in the 1830s enough stone was transferred from the Abbey, where Thomas and Jane lived, to the house at Edgarley where John and Maria lived, to create the fascinating replica of the Abbot’s Kitchen that stands in the grounds by the pond. The family called it “The Hermitage”. Now known as the Summer House, it was restored in 2008–10 by Millfield Estates, at the instigation and under the supervision of the then headmaster, Kevin Cheney.

As time went on, Thomas devoted more time and energy to the affairs of business, becoming an owner and the manager, as he was to be for the next 33 years, of the town’s Stuckey’s Bank, which had absorbed the Bank of Reeves and Porch in 1835. He also entered into community life. When the Municipal Corporations Act was passed in 1835 he was elected a member of the new Town Council, and on the following day he was unanimously chosen to be Glastonbury’s first Mayor at the age of 27, which perhaps is hardly surprising as he was the town’s leading landowner.

Thomas Porch was elected Mayor three more times, in 1847, 1853 and 1861. He finally retired from the council in 1865, though he was soon succeeded there by his eldest son, Albert.

At some stage Thomas presented the town with two fine mayoral chairs, inscribed with his name, which are kept in the Council Chamber of the Town Hall and still used in the annual Mayor-making ceremony.

Porch–Reeves tension?

Thomas and Jane continued to live at the Abbey House, where all their eleven children were born, until around 1851, when the Porch finances were caused serious damage, inflicted, so the family say, by a Taunton solicitor on the Reeves side of the family, who cheated Thomas Porch out of a large sum of money.

The truth may be a little more complex. Firstly, the researcher Dr Adam Stout has recently unearthed a “Deed of Gift” dated 13 November 1848 in which John Fry Reeves gives his younger sons a large amount of property in and around Glastonbury, including the Abbey and the Abbey House, said to be “now in the occupation of Thomas Porch Porch Esquire as Tenant to the said John Fry Reeves”. Eighteen months later, the Abbey, clearly never owned by Thomas, who was admittedly already quite wealthy from his Porch inheritance, was put on the market.

Secondly, it may be significant that John Fry Reeves had already decided to move away in the early 1830s, committing his future, not to his lucrative home town of Glastonbury, but to Taunton. Had his reputation been tarnished by the accusations of a number of Glastonians who had found themselves in debt to him and, in one infamous case, been bankrupted by him?

Then soon after 1851, when all the Reeves were living in Fitzhead near Taunton, with the Abbey sold, proceedings began against them in bankruptcy court, due to losses in the Somerset Coal Mining Company. Furthermore, John Frederick Reeves was imprisoned for fraud. It doesn’t get any better: John Fry Reeves died of “apoplexy and paralysis” a few years later in London with his daughter Julia Maria by his side. His wife Maria lived on until 1864 and was buried at St Benedict’s in Glastonbury. Did she and John Fry Reeves come to lead separate lives?

One cannot help but wonder how Thomas Porch Porch, with his three Reeves brothers, John Frederick (who attended Charterhouse like his elder brother), Orlando and Archibald, and a Reeves sister, Julia Maria, felt, as the star of his new family rose and that of his original family fell, along with their finances.

Notwithstanding, the Porch name doubtless sheltered Thomas from all this to a certain extent, and gave him the opportunity to seek new alliances.

Bagehot and Austin connections

So in 1866 Thomas and Jane’s eldest son, Albert, born in 1833, married Margaret Bagehot — of the wealthy Bagehot family of Langport — daughter of Edward Bagehot (pronounced badgeut) and first cousin of Walter Bagehot, then editor of The Economist, and prolific writer on literature, government and economic affairs. Walter’s father, Thomas Bagehot, was managing director of Stuckey’s Bank.

The marriage celebrations began ominously, however, as reported by the Central Somerset Gazette of 4 August that year, when two soldiers, who had obtained permission to fire a cannon to mark the happy event, suffered the most horrific injuries when the cannon misfired prematurely. Neither was expected to survive. Was this a portent of the unhappy outcome of Albert and Margaret’s union?

Not long after, the Abbey presented Thomas with another opportunity to strengthen the family’s fortunes, for the Abbey estate was now owned, and the Abbey House occupied, by the Austins, originally a farming family from Tilham Farm, Baltonsborough, some of whose enterprising members had made their fortune in Australia, first in Tasmania, then Victoria. This particular Austin, James, formerly Mayor of Geelong, had come home to spend his money and flaunt it!

Several Porches married into the Austin family, including Thomas and Jane’s sixth child, Reginald, who married Anne Rebecca Austin, daughter of James, in 1870. The wedding photo is one of a number which show the two families and their children in front of the Abbey House.

It is a sad sign of those times, however, that, despite the family’s wealth and advantages, of the eleven children born to Thomas and Jane, five died before their majority. Of the four boys that married, two had no issue, leaving only Reginald and his eldest brother Albert with heirs.

Thomas died just seven years after Reginald and Anne’s wedding and was much mourned by the community. The then Mayor described him in the local paper of 8 March as “a gentleman whom all could approach; he had a kind word for all, whether rich or poor, and by his urbanity of manner, his kindness of heart, his geniality of temper, he endeared himself to all”.

One interesting snippet from the mid-19th century, not directly concerned with the Porches, is that the son of one of the estate’s farmers, Thomas Millear, emigrated to Australia, hoping to make his fortune, like the Austins and others, and started a station (farm) near Willaura, in the state of Victoria. The Millear family still farms there to this day at Edgarley Station! Apart from an Edgarley Terrace in Fulham, southwest London, there seems to be no other Edgarley in the world.

Albert Porch

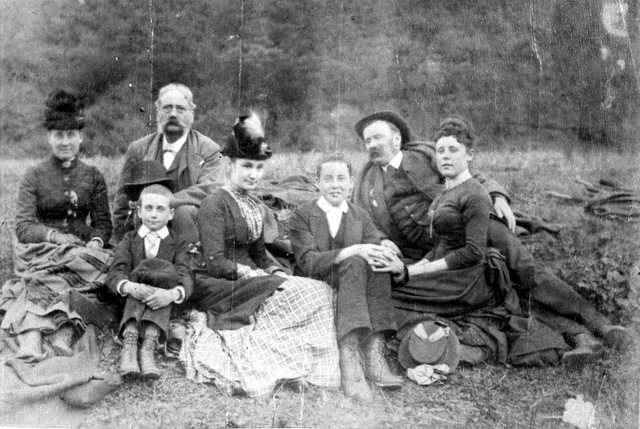

Back to the eldest Porch offspring, Albert. He and his new bride, Margaret, spent their early married life at Edgarley Lodge, a hundred yards up the road from the House. When his father, Thomas, died in 1877, they took up residence there, as befitted the new squire. The photo of the young family on the lawns of the Lodge must have been taken shortly before they moved. The children, in order of age, are Edith May (the eldest and the only daughter) about 10, Cecil 4, Robert 2, and baby Reginald (Reggie).

At this time Albert had already been on the Town Council for about six years and was to serve another thirty. He was not an academic like his father, having been educated locally at Bruton and set on living the life of a country gentleman, but he followed in Thomas’s footsteps by being first elected alderman, and then Mayor in 1879, 1892 and in the fateful year 1897.

Margaret too played her part in public life in no small way, particularly in her involvement with St John’s Church, where her husband was churchwarden, and in the founding, during Albert’s third term as Mayor, of the Victoria Nursing Home in Glastonbury, of which she was president, a post she held until her death in 1930.

Albert and Margaret’s early years at Edgarley House saw great improvements in the care and development of the estate. They developed particularly fine kitchen gardens to the north of the house and ornamental gardens to the south. It was not long before Albert’s attention moved to the house itself, although the planning process may have begun before Thomas’s death.

Before we leave this happy scene and proceed to the enlargement of the house, it is worth noting that in this photo we have the first appearance of the person who was to bring the family down, within just 20 years, by a crime that would be headline news around the world — Edith May Porch.

Enlarging the house

However, all for a time was rosy in the Porches’ garden. Albert took little time to enlarge the old Georgian house by building a west wing in the 1880s (1882 is a date readily seen on guttering and eaves) lending it a grandeur, in true Victorian fashion, to reflect the pre-eminence, wealth and influence of the Porches, although there were some members of the family in later generations who felt it spoilt the proportions of the original house.

A fine wooden staircase was introduced, in a grand entrance hall, with a fireplace embellished by a stone relief of the Four Evangelists, presumably transferred years earlier from the Abbey and repositioned. The stairs led first to a mezzanine level with a billiard room, drawing room and library, then upstairs to a gallery and ample bedrooms, with dressing room and lavatory, and a boudoir with windows of medieval glass, also perhaps from the Abbey. Upstairs in the older wing were more bedrooms, one with a fine ensuite bathroom, and a nursery.

On the ground floor were kitchens and service rooms and a dining room that opened onto a terrace through three French windows. There, also, was “Mr Porch’s room” (presumably for old Thomas Porch Porch), complete with medieval oak beams that had survived the axe of an earlier Porch! The main entrance switched from south to north, allowing the family to enjoy the privacy and warmth of the patio leading onto the formal gardens.

Who the architect and builder were has not yet come to light, but part of their instructions were to add the final stamp of a prosperous family, in the form of the stone sculptures of the Reeves “Pelican in her Piety”, the Porch wolf and the Bishop’s mitre — a clear reference to the Abbey and the mitre-wearing abbots.

Returning to Albert and Margaret’s family, there is no record of the education of Edith, the eldest, and one must suppose that she was educated at home, unlike the eldest son, Cecil, who, after prep school in Clevedon, followed his father to Charterhouse, and Robert and Reginald, who were sent to Malvern College. The photo shows some of the happy family on a picnic in about 1884.

Carew and the heiress

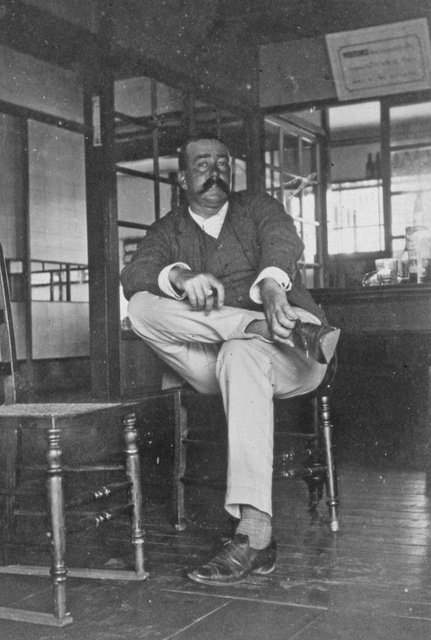

It cannot have been long after this that Edith May Porch had her first fateful meeting with Walter Hallowell Carew, whom she married, almost certainly against her parents’ wishes, on 2 May 1889, the day after her 21st birthday.

Besides being 15 years older than Edith, Walter was a man with something of a past and no money, despite having a famous grandfather, Admiral Sir Benjamin Hallowell Carew, who had served with distinction under Nelson. There had been money in the family but it had been squandered on gambling. Walter’s father, an army major, and mother lived a modest life in Exmouth.

The difference in age and fortune (Edith was an heiress with a personal income of £400 a year), combined with Walter’s reputation as a womanizer, held no sway with Edith, and they were married with great ceremony at St John’s, Glastonbury, as reported in full by the West of England Advertiser a week later:

The bells rang out merrily, and the children from the bride’s class at Sunday School strewed flowers in their way. The town was gaily decorated with flags and bunting. After the ceremony, a large company were entertained at Edgarley House, and in the afternoon the happy couple left for North Devon, where they intend spending their honeymoon. The presents were both handsome and numerous.

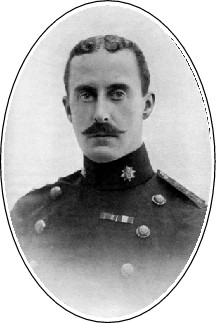

The “happy couple”, having then sailed off to Malaya, where Walter was a minor civil servant, were forced, because of his poor health, to leave for Japan. There in 1890 Walter took up an appointment as manager of the United Club of Yokohama, a thriving international port with a large European population, mostly male and mostly British. The photo of Walter was actually taken at his club.

We may suppose perhaps that Albert and Margaret viewed the removal of the newlyweds to such a far-flung place with mixed feelings; if their son-in-law turned out to be the cad they suspected and if the marriage foundered, at least the resulting gossip and awkwardness for one of Glastonbury’s respected families would be diluted by the time the news got back home. How misplaced such reassurance would turn out to be!

Life in Japan

In Yokohama, Edith Carew occupied her time with her horses — she was an excellent rider — and her dog and a social life centred around the expatriate community. In 1891 she gave birth to their first child Marjorie, or Mardie, and a year later a son, Benjamin.

However, Edith’s return to England for most of the following year, 1893, may well indicate a drift in the marriage from which it never recovered.

A photo shows the whole Carew family outside their house in Yokohama in 1896, when Edith’s younger brother Reggie, now 19, came to visit. In the picture he is sitting on the step with the dog. Would it be too easy to claim, by looking beyond the typically staid, strait-laced pose of the age, that one sees in their eyes any hint of the dark ten years to come, where no male member of the family group is still alive and where one of the females is serving a life sentence for murder?

The other women in the photo are two of Edith’s cousins, one of whom was a bridesmaid at her wedding, and the children’s governess, Mary Jacob. Mary, the daughter of a Somerset farmer, had lived with her aunt and uncle at Strathalbyn in Baltonsborough, just a few miles from Edgarley, after the death of her father. Recommended and hired by Edith’s own mother Margaret, Mary would play a major role in the drama that was to unfold in the autumn of that same year.

Mary arrived in May 1896 to find serious problems in the Carew marriage, as we know from Edith’s diary, now in the National Records Office. There were rows and disputes about money — Edith’s money sent from Edgarley but paid into Walter’s account, from which he paid her an allowance. Mary found love letters in Edith’s wastepaper basket. Whether this, together with Edith’s apparently long line of admirers, was her ploy to gain Walter’s attention is not clear, but it did not work. He was relaxed about her male friends: he even gave them pet names like the Organ Grinder and the Ferret!

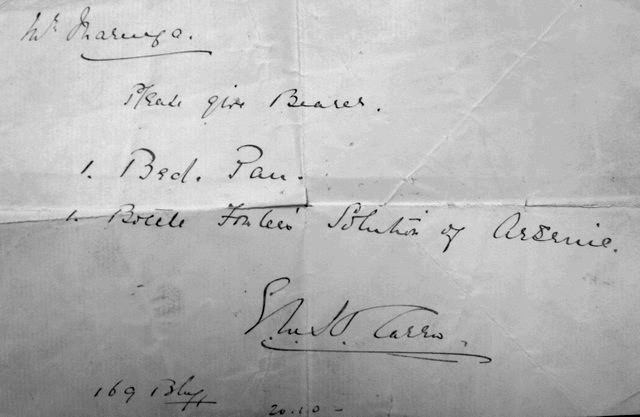

Walter spent increasing amounts of his time attached to a bottle. Furthermore, he was self-medicating with Fowler’s Solution, a popular arsenic-based tonic and palliative for gonorrhoea, a condition from which he had been suffering for some years (there were almost certainly children of his in Malaya). It was Edith who played this particular Victorian wife’s role of secret provider to perfection, acquiring from local chemists, during the space of 10 days in October that year, enough of the solution to kill four grown men.

On Thursday 15 October 1896 Walter arrived home feeling “out of sorts”, according to the entry in Edith’s diary. He was destined never to leave the house again except for his removal to hospital a few hours before his death exactly a week later.

A post-mortem revealed no obvious disease. However, organs sent for analysis showed the presence of arsenic, and an inquest which ended a week later concluded that Walter had died of arsenic poisoning and that Edith had a case to answer, having been the only person to nurse her husband in his final days.

Edith Carew on trial

The trial, before a five-man jury all chosen from the social circles in which Walter and Edith moved, began on 5 January 1897. News of it immediately flew on the wire around the world and took comparatively little time to reach Glastonbury, where a sense of disbelief and shame fell upon the community whose Mayor was the father of the accused — and this in the year of Queen Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee!

Hope was kindled by the disclosure, in Edith’s evidence, of a sinister figure who called herself Annie Luke (the name of one of Walter’s old flames in Devon). Annie had apparently turned up in Japan and visited the house asking for Walter, leaving cryptic messages and, after his death, intimating responsibility for the murder. Walter even wrote to her. The jury was unconvinced by this, not least because the mysterious lady had been seen by no one save Edith, and they suspected her of fabrication.

As a result and because of Mary Jacob’s evidence against Edith with the love-letters, the defence counsel, no doubt pressured by Edith, started a private prosecution against Mary Jacob, for the murder of Walter Hallowell Carew on the grounds that she had been having an affair with him — which may well have been true, but which surely would have been a stronger motive for Edith than Mary. This bizarre situation of one murder trial within another made very slow progress in the second because Edith had to keep appearing in the first!

News of the case continued to wing its way around the world, and back to Glastonbury, until 4 February 1897 when this report appeared in a quiet corner of the West of England Advertiser:

The Domestic Tragedy in Japan: Mrs Carew sentenced to death

The trial of Mrs Carew poisoning her husband concluded today. The case has extended over four weeks, the Court having sat 21 times. The judge, in his summing up, laid stress on the evidence against the accused, and, after retiring for 35 minutes, the jury returned a verdict of guilty.

The prisoner was condemned to death. The sentence is subject to revision. The prosecution does not intend to proceed with the case against Mary Jacob, the nursery governess.

The news of the result of the trial was received at Glastonbury about mid-day on Tuesday, and caused a profound sensation, and the deepest sympathy is felt with the Mayor [Albert] and Mrs Porch, the parents of the unfortunate woman, who is only about 25 years of age. The tragic affair has cast a gloom over the place and has brought dire distress and unconsolable sorrow on the family, who are held in the highest esteem in the country. Soon after it became known that Mrs Carew was involved in a serious charge, the Mayor and Mrs Porch sought retirement at Bournemouth, and it was here that on Monday Mr H. W. Swayne — a member of the firm of Mr Porch’s legal advisers and a personal friend — went to inform them of the overwhelming nature of the news conveyed in the following telegram which had been received: “Yokohama wire advise Porch Edith convicted. Sentence requires confirmation of British Minister.”

The case made it into the New York Times although it seems not to have picked up the fact that three days later Edith’s death sentence was commuted to life imprisonment with hard labour, thanks to an amnesty decree by the Japanese Emperor to mark the death of the Dowager Empress.

After transfer to a Hong Kong prison and a failed request from her parents for leave to appeal against her sentence, Edith was shipped back to Britain and taken to Aylesbury Prison late in 1897. Shortly after, the family, supported by Walter’s family and many prominent local people, petitioned Queen Victoria for a free pardon. This was given serious consideration by a committee whose evidence was examined by a top forensic scientist of the time, Dr Sir Thomas Stevenson. Unsurprisingly perhaps, he concluded that, since Edith was the only person to have the means and the opportunity to kill Walter and since no one commits suicide by taking small amounts of poison over the course of a week, the verdict should stand.

Prison and after

Edith was to spend a further twelve years in prison until her release in October 1910, having served the equivalent of twenty years with remission. Her time behind bars was not uneventful. First, she wrote poetry. One of her poems, The Pariah’s Lament, begins “Outcast and dreary, hungry and weary, always and merely — a Pariah” and, a few similar verses later, it ends in the declaration “Providence made me — a Pariah”. Indeed, apart from a certain self-pity and sadness for her family, there was no apparent acceptance of guilt, feeling of contrition, or even anger in anything she wrote in prison. In fact, she was said to have charmed everyone she met there.

Edith also starved herself for a time in 1906, doubtless due to the grief she and the family suffered when her only son, Benjamin, following the career of his great-grandfather Admiral Sir Benjamin Hallowell Carew by becoming a naval cadet, developed complications from an ear infection at the Royal Naval College at Osborne on the Isle of Wight and died, at the age of 13. The obituary from the local press does not list Edith among the mourners. If she did attend, it must have been incognito and under guard.

.jpg)

The effect of all this on Edith’s parents will have been devastating; in fact Albert was said to have rarely set foot outside Edgarley in his later years. As if the imprisonment of their only daughter and the premature death of their only grandson were not enough tragedy for this apparently kindly old country gentleman and his wife, news of a third catastrophe came shortly after. This was the disappearance of Albert and Margaret’s third son, Reginald, who had gone to Japan in 1896 to study butterflies, but had unwittingly become the only family witness of the poisoning of his brother-in-law and the trial and the conviction of his elder sister for murder, all of which would have had a profound and lasting effect on him.

“Reggie” Porch was an adventurous but perhaps rather aimless young man who, after his fateful trip to Japan, had headed off to North America in the early years of the century, ranching, trapping, trading, and working as a Mountie. Then in April 1906 he arrived in San Francisco at the precise moment of the devastating earthquake. Having survived it, he, crucially, lost all his money in the chaotic aftermath. Writing a desperate letter home, he was wired more money from Glastonbury, but was never heard of again. The family firmly believe that he was gunned down while trying to fight off robbers.

Edgarley sold

Edith herself may have returned to live at Edgarley for a while after her release in 1910. However, when her father died in 1914, the estate was sold off and the whole family moved away for good, doubtless still reeling from the events of the last 20 years. (Incidentally, the last secular owner of the Abbey, Stanley Austin, had sold the Abbey estate in 1907 and moved away to Taunton, where he lived quietly until his death, some years later. Stanley’s obituary in the local paper dwelt principally on his involvement with the Glastonbury town band!)

After the Porches sold up, Edith first moved to Chippenham, not far from her mother Margaret in Bath, then to Dinas Cross in South Wales, where she and her daughter, Mardie, who never married, lived a quiet life, surrounded by the sea and the Bedlington Terriers that Edith bred, until their respective deaths in 1958 and 1978. Edith never remarried.

But in the 1920s they were joined in South Wales by one other member of the Porch family, a little girl called Pansy, a grandchild that Albert never knew.

Cecil Porch

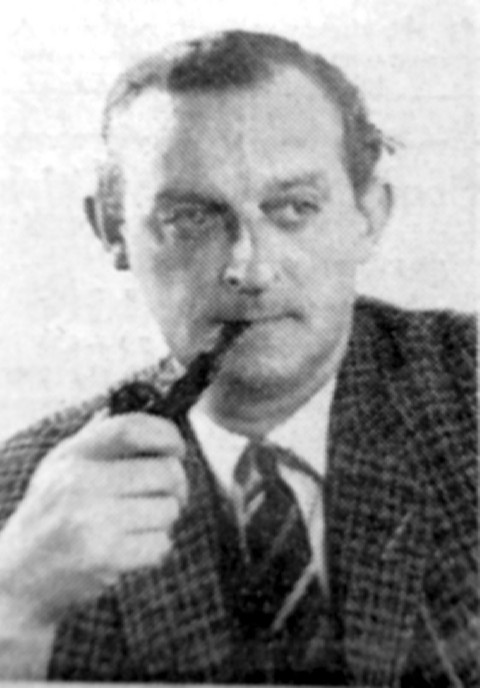

Time to introduce Cecil, the eldest of Albert and Margaret’s three sons.

Cecil seems to have been the black sheep of the family, who is sent away to board at age eight in Clevedon, then Charterhouse, and features in no family photos after infancy, no census lists at Edgarley or any legal documents seen hitherto. And yet Cecil was a brave soldier, who distinguished himself as lieutenant in the East Surreys in the Boer War. In fact on returning home to Glastonbury in the spring of 1900 after being wounded at Spion Kop, he is given a hero’s welcome by the townspeople and local dignitaries. As the local paper reports:

All over the town flags were hoisted and bunting displayed, the bells of St Benedict’s set ringing with joyous peals and crowds assembled to see him pass. As the train steamed in, the town band played Home, Sweet Home.

How poignant this show of support and solidarity must have been for Cecil’s parents when they reflected on the last time the town had turned out for the Porches, some 11 years previously — at Edith’s wedding, also in springtime.

The West of England Advertiser does not leave it there, for over the next few issues it printed long interviews with the highly decorated but diffident soldier about his service to the country in Natal.

Africa seems to have cast a spell over Cecil, for we next see him there in 1910, in the company of a leading suffragette and authoress, Edith Maturin, whom he meets in Rhodesia. In fact, Cecil is quoted as a “correspondent” to Edith’s “misconduct” in her divorce from her first husband, Colonel Fred Maturin of the East Surreys! (The headline in the newspaper article reads “Adventure of a Colonel’s wife in Rhodesia”!)

It is in that same year, 1910, that Edith and Cecil, with two others, went on a prolonged safari, described eloquently and at length in Edith’s book Adventures Beyond the Zambesi, where we read something of his character and bearing, and the general popularity of army officers. She writes:

We all began by being deeply touched by our undoubted popularity, until it began to dawn on us that we were taken for semi-millionaires wandering the earth for pleasure — and everyone wanted a slice out of the plum-cake. Apparently only Dukes of Westminster and others like them come up here on shooting trips.

Cecil looks so distinguished, also soldierly! A real live British officer in these regions is rather rare, and, of course, all the world over, the common idea is that the British officer has money. It’s an extraordinary idea, for he generally has none, but it’s partly his own fault, for he can’t help looking and acting like it, and yet sometimes has no idea that he does. The “airs” he is accredited with, he is often quite unconscious of. They are simply a part of his life of simple adulation, ease and pleasure; his habit to command and be obeyed since he first joined as a boy of eighteen; the military etiquette and politeness which are the air he breathes. The attentions of everyone, from mamma who wants to marry a troop of daughters, and papa who likes the regimental port, ... The same with the tradespeople round. Everyone is polite, sweet and complaisant to the generous and considerate military officer of Cecil’s type, and life is more or less a path of rose-leaves, till you leave that charmed regimental circle and rub shoulders with real people who have to struggle and push to live at all.

Cecil and Edith enjoyed an exciting and often idyllic time along the Zambesi, but their marriage was not to last and there were no children from it. Whether it was interrupted and changed forever by the 1914–18 war, like so many others, is not clear, but true to his character Cecil wastes no time in enlisting, commanding the Tyneside Scottish, 23rd Northumberland Fusiliers with the rank of lieutenant-colonel, and being awarded DSO and Bar, for conspicuous gallantry, at Armentières and Arras.

But for the Great War, life might have been so different at Edgarley, for one suspects that Cecil, the eldest son, was the kind of man to shrug off the past, perhaps the true heir in spirit to the Edgarley estate. We can picture him, shooting, fishing, playing the part of the country gentleman, living the life of landed gentry and thumbing his nose to convention as he did later on at his Sussex golf club, when tongues were wagging about his private life. But Cecil, without money, without a wife, a family or a settled lifestyle and having been away for so long, was doubtless considered just too much of a maverick and so never became part of the equation. He even seems to have been omitted entirely from the legal documentation on the sale of the estate. In any case, at the time of his father Albert’s death, Cecil was too busy serving king and country.

Having been wounded three times, the last severely, he was invalided out of the army in 1917. Cecil very possibly found it difficult to adjust to civilian life, and he proceeded to have two children, neither of whose mothers he married. It is the first of the children, Pansy, who went to live with her Aunt Edith, now out of prison and living in South Wales with her own daughter Marjorie and their Bedlington terriers. Cecil’s second child by another woman, a son, Richard, arrived just five years before Cecil died in 1933.

Younger brothers

By that time, of course, the corridors of Edgarley had long ceased to ring with the laughter of Porch children. Cecil’s younger brother, Edward Albert (Bertie) Porch, MC, had a successful military career as a colonel in the Indian Army, but had no children from his two marriages.

The second of the three brothers, Robert (also known as Robin or Judy, because of his nose), having taken a classics degree at Trinity, Oxford, had already embarked upon a long and successful career as a much-loved teacher at Malvern College. He was a fine cricketer and, when school duties allowed, played as an amateur for Somerset until 1910. He had the dubious distinction of being in the field at the County Ground, Taunton, for the whole of Archie MacLaren’s record-breaking innings of 424 for Lancashire in 1895.

Robert’s marriage to Kathleen Hector produced four children. His second son Alec, the former keeper of the family records, followed in his father’s footsteps as a pupil at Malvern, as a Classicist and in his life as a schoolmaster, becoming the headmaster of an independent school.

However, Robert and Kathleen’s eldest son, Robin, revived the Edgarley Porches’ connection with the area by returning to Glastonbury in 1962, after retiring from the Colonial Service. Robin immediately involved himself in the local community, through sport — he was good cricketer, like his father — and politics. He even made his home at Southfield, the former residence in Bere Lane of Dorothy Porch, daughter of one of Albert’s younger brothers. (Southfield was replaced in 2004 by twelve modern houses in a development named Porch Close.) Sadly the new Porch connection was not to last: Robin’s life was tragically cut short by cancer in 1969 when he was just 49, only a year after being elected a town councillor.

Curse or care?

So how should we view the Porches of Edgarley and their story?

Earlier, the possibility was raised that their fall might be something more sinister than simply fate, because of a curse that is said to be laid on secular owners of the Abbey. Indeed, on face value the fortunes of the Porches, the Reeves and the Austins all declined, the Porches in a dramatically sad fashion, as we have seen.

Whatever the truth of it, evidence suggests that all three of these families cared for the Abbey in a way it probably never had been since the Dissolution. For example, the Revd Richard Warner, in his 1826 History of the Abbey of Glaston and of the Town of Glastonbury, pays tribute to John Fry Reeves for his “creditable zeal for the preservation of memorials of former ages for the inspection of the curious and the contemplation of the thoughtful for ages to come”. Likewise, J. G. L. Bulleid, a founder of the Glastonbury Antiquarian Society, writes in The Bath Chronicle and Weekly Gazette of 2 April 1896 praising James and Stanley Austin, the last secular owners of the Abbey, for their care of the remains.

As regards the Porch family, it cannot be denied that Thomas and Albert served the community in generous and wholehearted fashion over many, many years. Other members of the family, as we have seen, fought for king, queen and country and devoted their lives to educating its young people.

And who would deny that in building the truly unique feature they called The Hermitage, the family preserved a significant quantity of Abbey stonework, which may otherwise have been lost to posterity, like so much else?

The evidence would suggest that this once distinguished family has more than paid their due.

The latest in the extraordinary saga of the Porch family

In 2015, there came a new and almost unbelievable disclosure about the family from Julian Wood, a hitherto-unknown great-great-great-grandson of the last squire, Albert Porch.

Julian revealed that when Albert was 17, he had a relationship with an Edgarley chambermaid by the name of Edith May Small.

Edith May Small became pregnant by Albert and was sent away to have the child, a little boy, whom she named John Albert!

And as we know, some years later, Albert and his wife Margaret would name their first child, a baby girl, Edith May!